The other things I wrote when I put the word “fear” on the screen:

The latest word is that we must live with the virus. Some of us have postponed our date with it, but it will come, and even the vaccines cannot guarantee the outcome of that destiny. Sooner or later, we will each have our encounter with coronavirus as it morphs from one variant to another. As I commented after looking at the first curves used to justify the lockdowns: The shape of the curve can be changed, but the area under the curve, representing death and illness, stays roughly the same. The reason this coronavirus is so different than others, so much more persistent, and so accurately aimed at human beings, is a matter that some continue to debate. But the virus, and fear of it, like the fear of death, will always be with us. It is a companion that can rule our life or take a seat in the back as we try to continue the life we had before.

Without question, there were times at the beginning when I gave in to fear. There were nights when a sniffle or two or a headache would make me check my temperature compulsively. We worried and prayed for those in our lives that were vulnerable. We ticked off the days after we were with someone who came down with it. The pictures from the hospitals were and are enough to scare you. The death toll could be argued, but not argued away. We were passed over, but many were not.

For me, the antidote to fear was gratitude. It started with my gratitude for those who had no choice but to conquer their fear. They were all around me, even in a society supposedly locked down. They stocked the groceries and staffed the pharmacies. They cooked in hamburger stands and delivered pizzas. They picked up the garbage and delivered the mail. The liquor stores and marijuana dispensaries were open for business. Many ordinary people were required to just get on with life. So they conquered their fear and kept living. Why couldn’t I?

To live through this without fear, one must make peace with death, and that is a peace everyone can only make for themselves. I believe I have no entitlement to each new day of my life. I have been spared by Covid, but also from accident or other disease these past 18 months. At 66, having lived through an immunocompromising disease, I could have only a few more years, or as many as 30, but neither the length of my past or present is my expectation. There are other risks that probably pose a greater threat to me at this point. Rather, it is my responsibility to be grateful for the joys of each new day, and to count the blessings of the past. I feel I’ve had more than my share of life, having lived to be a father and grandfather, having at least four separate acts to a life lived in a country that supposedly had no second acts. I have been blessed by my faith to be at peace, and to be grateful for what I have, and to look forward to the possibility of a fifth act.

My own fears have been easier to conquer because I live a wonderful life. I live and work in clean, well-ventilated, uncrowded places. I have access to nutritional and fitness guidance that increases my resistance and strength to oppose any disease. Whenever I do encounter a health problem, I have immediate access to resources that others struggle to connect with, including immediate access to cutting edge treatment. I have a wife who will not leave my side. Nor I hers.

For these reasons, my own fear is usually in check. Yet that is the beginning of the problem of fear. I have learned that it is almost more important to act in accommodation of the fears of others.

Accommodating the fears of others is a big job at times. It starts with the question of whether someone else is even comfortable being around you. This requires being sure that others are still comfortable with what used to be common touches of hands in greetings and goodbyes. Then there is the decision to mask or not, to stand outside on the lawn or go into the living room. Can the other person get together for dinner somewhere or just talk on the phone?

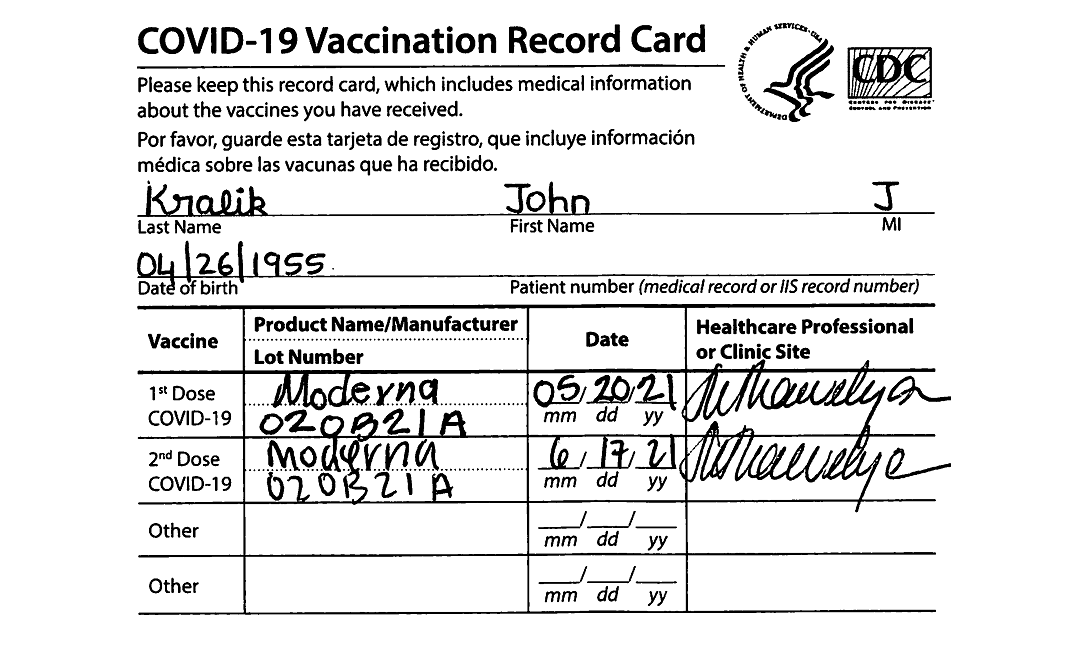

Next there is the issue of whether any of activities of work, learning or life can occur in the absence of a vaccine. All of these are issues needing accommodation. (I have had the vaccine and urge you to do so. It seems to make people feel more at ease, and I can’t afford to lose more friends.)

I have learned that individual choices cannot be ascribed only to fear. There are plenty of voices with scholarship and experience to counsel in favor of the most extreme measures. Then there is the media that conveys these messages. We choose the news we watch based on our fears, and after we watch we feel more fearful than ever. You could try turning the channel, and you may find a channel that will tell you that you would be crazy to be so fearful, but that would make you afraid of the people who are telling you such things.

Perhaps the most important accommodation I have learned is that it is best not to categorize others as fearful when speaking with them. But fear must be confronted, however gently.

Because the virus and the fear it has caused will always be with us, each of us will need to decide how much of our life to cede to fear of our inevitable encounter with past, present or future variants. Each of us will have to decide how much to accommodate the fears that others have of that encounter.

Yet there is another, perhaps more important, decision. No matter how we decide to address fear, we must be respectful and decent to those who answer those questions differently than we do. We need to remember that many of these are personal decisions, made under difficult circumstances, with conflicting information.

Years from now, when this is all over, we will gloss over some of the pointless nature of our fears. Already, billions of dollars of hurriedly installed plexiglass is being taken down. We all know people who washed down their groceries after requiring they be left outside by gig workers in the early days of the pandemic. I don’t think anyone does that now. Only in retrospect will we truly know what worked and what didn’t. For example, the verdict of history is apparently that the gauze masks that were a symbol of the 1918 pandemic response were completely ineffective. (J. M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History at 375.) (Penguin 2018) (“The masks were useless.”)

What will be harder to live with is the times when we allowed our fears to cause us to behave in ways that were indecent to our fellow man. We will have to live with the families, friendships, churches and businesses destroyed by fear.

Whether we are dealing with our own fears or the fears of others, we must behave decently. Many have used, and are using, the pandemic as an excuse or a pretext to behave indecently to their fellow man or advance agendas of power. For decades, the popular culture has portrayed the infected as filthy, mindless, murdering masses as in the endless carnage of the Walking Dead. This fear is deeply imbedded in us, and we may be going along without thinking twice. Clearly, we no longer listen to the religious call to “Fear not.” It is no surprise, therefore, that the pandemic has shaken norms of decency in every aspect of our society. And with each wave, more norms of decency fall by the wayside. It is no longer unthinkable for people and governments to behave in unimaginable ways.

Of course, decency was already under attack. We had lost our way in so many ways even before all this began. Returning to the way things were in early 2020 is not much of a pathway back to decency. If we are to restore decency, we must go back farther in history to seek the norms of decency upon which to order our behavior. Those times were not Utopian, but they bear examination. It was sexist, of course, but humanity was better when women and children boarded the lifeboats first.

We have been divided into those who wear masks and those who won’t, those who have vaccines, and those who don’t, those who want to start living like before and those who have decided not to ever live like that again. These divides are perpetuated by greed, avarice, and the hunger for power. Politicians manipulate our fears to gain power for themselves. Journalists exploit fear for ratings. To business, fear is an economic opportunity to crush weaker competitors. The rest of us suffer the damage because we must live on either side of the divides created by pursuit of these agendas.

We really can’t afford to have so many people on either side of those divides. I submit that it is time to stop giving away even an inch of our decency to fear.

Fear. Try putting it on paper. See where it takes you. How much are you willing to permanently give up in the cause of accommodating your fear, and the fears of others?

“Carry On” was the first song on Déjà vu, but it should have been the last. Let’s make sure that love is coming.

Recent Comments