Remember that moment? When this all started. When you knew it was going to be something.

Two days before, I had planned to be in New York City to run a half marathon. My bones had been hurting whenever I went over six miles. At mile ten, I felt really, really old. Then, to my great relief, it was cancelled. Not so bad.

The following Tuesday I became inessential.

Everyone was trying to figure out what they were supposed to do. You could start by finishing the things you never finished. I finished a novel I started in the 90’s.

Then, I started to sleep later, stay up later, and fill my days without actually doing anything.

It had been two weeks. I started to feel the ache of the lack of connection to people.

It had been years since I had been on Facebook, but I pondered going back.

There were many reasons I had stayed away.

At first, Facebook felt like the liberation of all thoughts you were holding inside, because it was too much trouble to trying to find a publisher. Now they could be published—to the entire world. Now they could be liked by all the people you already knew would like you more than they like other people. Others would finally realize your brilliance, your photographic skill, your amazing history, the fabulous dinner you’re having right now. Then there are the thousands of friends that have passed through your lives. You can remember part of their name. The computer can remember the rest. What do they look like now?

Honestly, I thought the whole idea was pretty neat–until I tried it. A few days later, I retreated in worry.

There was transparency, a whole new kind. But was that something I really wanted. Do any of us really live such clean and open lives that we can expose every aspect of our being on the internet? John Lennon and Yoko Ono thought they were ready for that type of exposure when they posed naked and put the results on their album cover. A few years later they were retreating and complaining that the press was trying to crucify them. A few years later John was shot by one of those with whom he had shared the details of his life.

The other problem with revealing so much is that people can end up knowing you better than you know yourself.

As I learned more about Facebook, I wondered. The basic building blocks of Facebook are supposed to be “friends.” But the company was started amid betrayals of friendship that left the founders at the wrong end of lawsuits with each other. It gave me a sense of an enterprise in which bad things would happen. The stock price would suggest otherwise, but I persist in the view that money isn’t everything.

Later, I returned to Facebook because I released a book. It felt it was my duty to try to promote it in what was now the best place to promote books. So I posted for a while. I tried to send only good messages. Luckily, my book appealed to the best in people, and I attracted really good people. There was a low point when a student who was writing a paper on my book asked me for help: “What’s the theme?”

Most persuasively, Facebook also awakened me to the concept of time suck.

I faded from Facebook. But with the coming of Covid I felt I needed to do something to reconnect, and to help others reconnect to the humanity that has been taken from us by the people who think they know better about whether or not we need human contact.

For each day, for fifteen days, I wrote a thank you note, and posted something about it.

My notes were mainly about the people who kept working. Being deemed inessential, I was fascinated by the people who were essential, and who were courageous enough to keep living their life in the face of media stories that were causing most people to feel they were risking their life by leaving their house.

The first brave souls I focused on were the people working at our regular hamburger stand. The drive-through window was open. Everyone was still working, bustling around the crowded kitchen. They weren’t socially distanced. They were not afraid. I wrote a thank you note to them. Then the pizza delivery restaurant that never stopped delivering.

My thank-you to the grocery store was particularly heartfelt. They were dealing with so many stressed and fearful people. Then people started wearing masks, a sign of fear that quickly spread. The shelves were restocked, the cashiers added it up, and we all kept eating. At a time when everyone was trying to avoid everyone in the neighborhood, grocery workers were required to come in contact with everyone in the neighborhood. The same for the men and women who delivered the mail, the bank and post office workers, the garbage pickup, the gardeners, the construction workers–all of these people never even thought of not showing up. They realized what we are all finally realizing months later: We have to show up. We have to go on living. We have to do our jobs.

I wrote my most important thank-you note to my wife. There was a moment that first day when we looked at each other and said, “Social distancing?” We laughed. For us, it was the beginning of the rebuilding of human contact.

After I completed my fifteen days, I left off Facebook. I wanted to get away from the eye of a storm of conflict that was tearing friends and family members apart, just as the original founders had been torn apart by the realization that their little program was worth more money than they could imagine. People were inflicting angry opinions on their family and friends, opinions honed by conflict professionals like lawyers and politicians who were trying to boost their presence by provoking anger and conflict.

I was and am still troubled by the growing body of evidence telling me the social media can be a virus that infects individual psyches, and a poison that ruins relationships. I have become fascinated by writing letters instead.

Now in October, I am tempted to return. Here’s why:

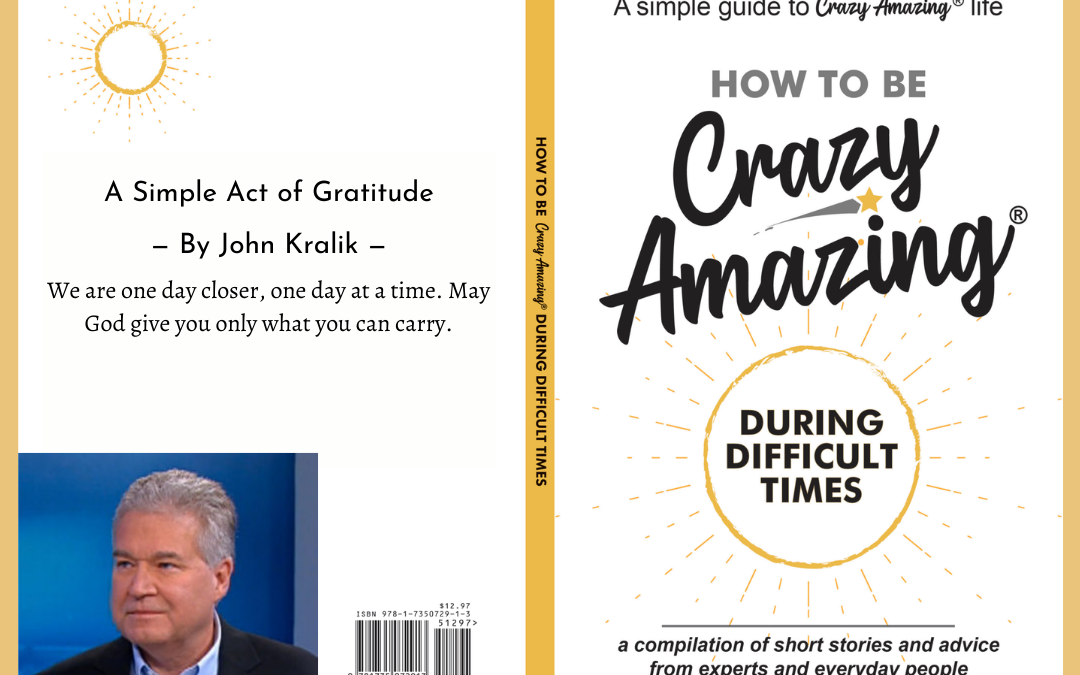

Author Ann Marie Smith, who has written a series of books on how to be what she calls “Crazy Amazing,” saw my posts from the early lockdown days, and made them into a chapter of a book, “How to be Crazy Amazing in Difficult Times.” The book has a plethora of wisdom from authors who advise people for a living. All proceeds are going to charity.

“How to be Crazy Amazing in Difficult Times,” has become an Amazon Bestseller, showing, I hope, that there is still a benefit to posting good things on Facebook.

If I return, it would be to post sparingly, carefully, and hopefully only to the good.

Facebook is not under our control, but we can make it better, or make it worse. That much is up to us.

Recent Comments