In the spring of 1970, David Crosby’s voice persuaded me to stop cutting my hair.

Before 1965, my hair had been short, but I was satisfied with it. The barber shop was a friendly place, and a young man could expect to read an entire good comic book and chew a few pieces of sugary bubble gum while waiting. The comics advertised innocent pastimes. I remember thinking of writing for the Charles Atlas booklet on how to build up your body, but no one was kicking sand in my face at the beach. The smell of overpowering hair tonic emanated from the raised chairs, which sat like thrones in the room. When elevated to the throne, the barbers treated us child characters with special care, aiming to please the waiting fathers, reading their more adult magazines.

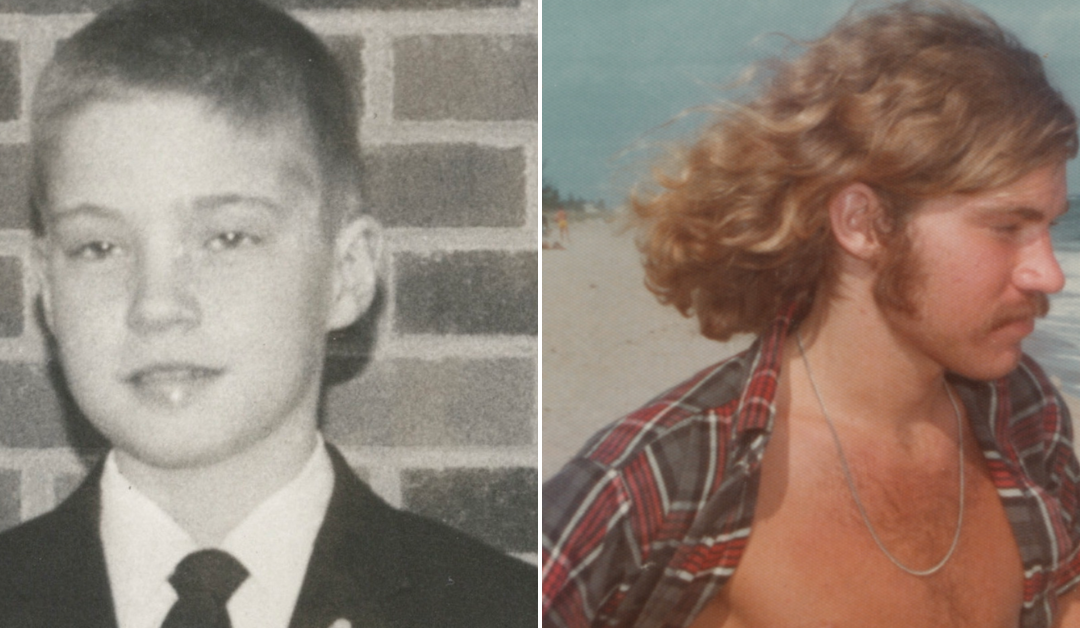

In 1965, I turned ten, and my parents sent me to boarding school. Haircuts became traumatic, at least to me. The nuns who ran the school managed the boarders’ haircuts with merciless efficacy. They didn’t cut it themselves, but they had a bulk discount at the local barber shop. They figured they could space the haircuts farther apart if our hair were cut as short as possible. Humorless barbers stubbed their cigarettes and quickly and thoroughly sheared our heads as if we were sheep. The nuns watched conscientiously to ensure totality and speed. Over the years, I learned to beg the barbers to leave some hair, and, despite the disapproval of the nuns, one of them would occasionally grant clemency to a tiny tuft of hair on my forehead in a style he called a “Princeton.”

After eighth grade, I returned home for a little less than three years, which did not go well for either my parents or me. I went once or twice to one of the local barbershops at my parents’ insistence, but barbershops were now traumatic places, filling me with resentment and anger at the last four years of assaultive sheering. I had outgrown the comics. I was reading real books now, books like “Slaughterhouse Five,” which caused me to question whether war would always be the answer, as the history books of my youth had caused me to believe.

As a high school freshman in the fall of 1969, I discovered FM radio. I remember the first FM songs from Rod Stewart’s “Gasoline Alley,” released in January 1970. These songs broke the confining forms of the songs on AM radio. I wasn’t sure whether Mr. Stewart was singing or shouting or screaming. He gave free rein to his musicians to play guitar in ways that broke away from the song’s structure. Something had been turned loose in music, and it was turning something loose in me.

Listening to the radio was not enough. I appropriated an aging turntable headed for the trash heap. It still played, albeit with a tinny sound that would be laughable today. It was more than enough for me. For the first time, I could possess and control music. I put the turntable on a desk in my room and played the two albums of the old AM material I had acquired at boarding school. It was time to buy some of the new FM music.

Though still 14 in early April of 1970, I managed to buy a ticket to see the movie Woodstock (rated R for hippie nudity). Alone in the theater that day, I saw the wild spirits that the new music had released. On the way home, I bought the album “Déjà Vu,” which I’d heard on the FM radio for the preceding few weeks. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young had sung tentatively at Woodstock. Steven Stills’ remark that they were “scared shitless” probably contributed to the film’s R Rating, and no one has forgotten it, but for me Joe Cocker and The Who stole the show.

“Déjà Vu” had a more brutal, more electric sound that dazzled me. After hearing it once, I immediately bought the previous album, the debut of Crosby Stills & Nash, and was awed by the beauty of “Suite Judy Blue Eyes” in tune and confident in contrast to the Woodstock performance. David Crosby’s oracular “Long Time Coming” echoed my despair the previous April when I had heard the news of the murders of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy on the AM transistor radio I had smuggled into my boarding school.

On May 4, 1970, four students were shot while demonstrating against the Vietnam War just thirty miles downstate from my home, at Kent State University. CSN&Y quickly released a song that voiced our dismay at the “tin soldiers” who had fired the shots. It offered no hope: we were on our own. A few days later, a beloved teacher at our school, a Holy Cross Brother who had brought joy to our freshman year by teaching us excellence on the basketball court, died of a heart attack while playing water basketball with some of my friends.

These events brought despair and a feeling of impending doom. We felt our own lives threatened. The seniors watched their draft numbers to see if they would go to Vietnam. Now it seemed that even if we avoided the draft and ended up in college, we could be shot by the National Guard. We learned the word apathy, which felt like the logical response to these events.

Déjà vu and CSN played over and over on my tinny turntable until the vinyl popped and crackled. The songs internalized into my being, and they remain as part of my soul. The songs did not engender my feelings as much as they seemed to explain them. We were “helpless.” A Stephen Stills song, “4 +20,” predicted how the next ten years of life would bring more despair, enough to ponder suicide. I thought of cutting out the ten years waiting for that to happen.

The noise of the group’s guitars was soon amplified by the sound of my typewriter, banging out reams of depressed, disheartened, and lonely poems that no one would ever read. The old typewriter made the desk and floor of my room shake with the tremors of my angry fingers.

These sounds frightened my parents. They had read how Jerry Rubin had incited the students of Kent State by telling them, “The first part of the Yippie program is to kill your parents. They are the first oppressors.” I suppose my high school years felt apocalyptic to them as well. Undoubtedly, they were convinced that listening to that music and writing on that typewriter were warping my mind.

Desperate to end the cycle of my mental deterioration, my parents constantly sought to interrupt my music and typing, escalating the battle between us. A day didn’t pass without them telling me to turn it off or down or to stop typing and go to bed. They began to come up with an increasing number of pointless jobs for me, work that would never end or seem to do any good as far as I could see.

In one of the vinyl grooves of the song “Teach Your Children,” there was a tiny half-second of David Crosby clearing his throat before beginning the next verse. It seemed like a flaw in the record, and I can’t hear it in the newly remastered and digitized versions now prevalent on the music apps of today. The timber of this sound was exactly the tone of my father’s voice telling me to turn off the turntable and come downstairs to mop the floor, mow the lawn, clean the garage, etc. Hearing this sound always made me look to the door of my room, which I had locked against my parents’ intrusions.

Fear was dominant in those times. Yet, in contrast to the helplessness extolled by Neil Young, one voice on the record invigorated defiance instead of apathy. David Crosby’s “Almost Cut My Hair” insisted he was “not giving in an inch to fear.” His reasoning for not cutting his hair was as thin as the wisps that his long locks would eventually become. He had promised himself a year? That was a line in search of a rhyme. He owed it to someone? But who? Who would care one way or another? I realized he didn’t need a reason. That was good enough for me. There was a warning, however, in one of his other songs: If you try to get elected, you will have to cut your hair.

I started another battle with my parents by refusing to cut my hair.

Yet the defiance in that song also encouraged me to find a way out of my depression. I started running, and my runs ran for more than an hour, an hour in which no one could reach me to do any chores. There were no iPods or even Walkmans in those days, so David Crosby’s voice just played over and over in my head. I decided not to give in to fear, but to keep running.

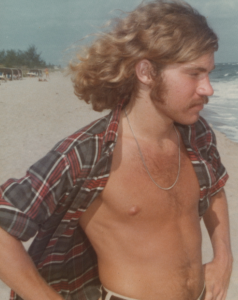

At seventeen, I left home and went to college a year early. And, for no good reason at all, I didn’t cut my hair for more than a year. I felt I owed it to someone.

In the succeeding years, neither David Crosby nor I were felled by tin soldiers or Nixon or bomber jet planes, though both of us were threatened by the consequences of the unrestrained desire for substances that dull the pain of existence. He survived to live responsibly with a second liver. I managed to keep my first one. I eventually did cut my hair. I was even elected a couple times.

No other music has ever touched me so profoundly. Strive as they might for the subsequent decades, individually or together, CSN&Y would never produce anything so immediate and stirring as those songs that played on my turntable in 1970.

It is the winter of 2023 and David Crosby is gone now; his defiant voice silenced. He outlived my parents, though not by much. Whatever you think of him, you can’t say he gave in to fear. His voice and those words returned to me during the Covid lockdowns, and I was grateful for them. I will continue hearing them as long as I can.

You are a beautiful and insightful writer. I have followed you for years. Keep on letting your talented freak flag flying…….

Thank you, Victoria, your encouragement means a lot

Yo Doc, a very interesting take on that era. As a child of immigrant parents who fled Communism in the 40’s and growing up in NYC, (as of course you know) my version of “rebellion” or perhaps ode to that era was wearing a green army fatigue jacket, jeans tucked into Frye boots while riding the subways to and from high school, my very nerdy high school. We thought we were so cool. Yes of course the requisite long hair as well. I remember when Nixon invaded Cambodia in May 1968, the kids used it as an excuse to “protest” by walking out of school. We didn’t go to Bryant Park to join the protesters, we went to the local “soda shop” (yes they still existed in those days) and ordered chocolate egg creams. Although I liked CSN&Y, I gravitated more to the harder, pulsing rhythms of the Stones, The Who and Led. In any event, great write up. We’ll have to talk again soon. Keep checking that Oura data! One thing, totally jealous of the fact that today you still need a talented hair stylist while I need only the tonsorial skills of a blind squirrel. Later dude.

Thanks, Norb. We must catch up soon. The hair is thinning now, but I am thankful for what I have. Hope the brain lasts as long. Doc

Happy Birthday John!!????????????

I truly enjoyed your writing! You have a way of bringing everything alive as you write. Your talent is amazing. Thank you for sharing your blog. How are you? I hope all is well with you! If you ever get to Houston, please let me know!!

Cece Guerra-Rice